What Are Ferns?Ferns are plants that do not have flowers. Ferns generally reproduce by producing spores. Similar to flowering plants, ferns have roots, stems and leaves. However, unlike flowering plants, ferns do not have flowers or seeds; instead, they usually reproduce sexually by tiny spores or sometimes can reproduce vegetatively, as exemplified by the walking fern.

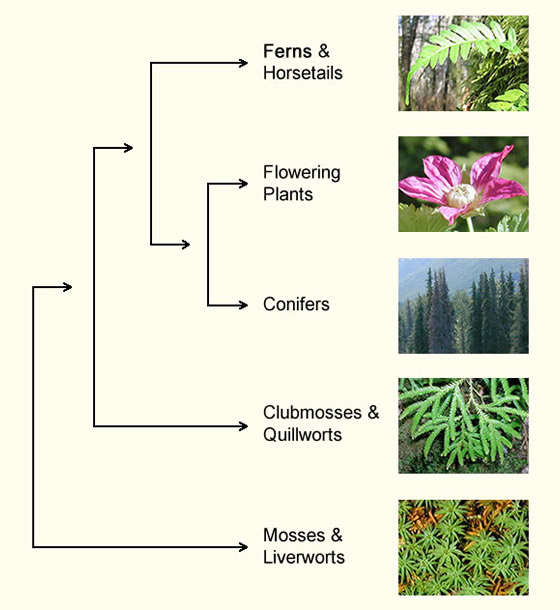

In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies”. Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to the horsetails. In fact, horsetails are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called “fern allies”, club-mosses and quillworts, are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below.

Fern Structure

Ferns can have some very unusual forms and structures. The following describes fern structure and forms that people typically encounter.

Leaves

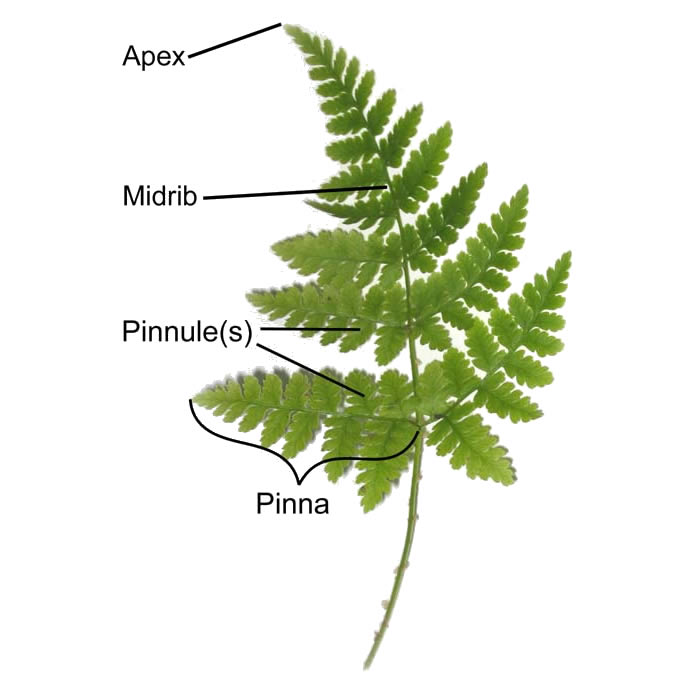

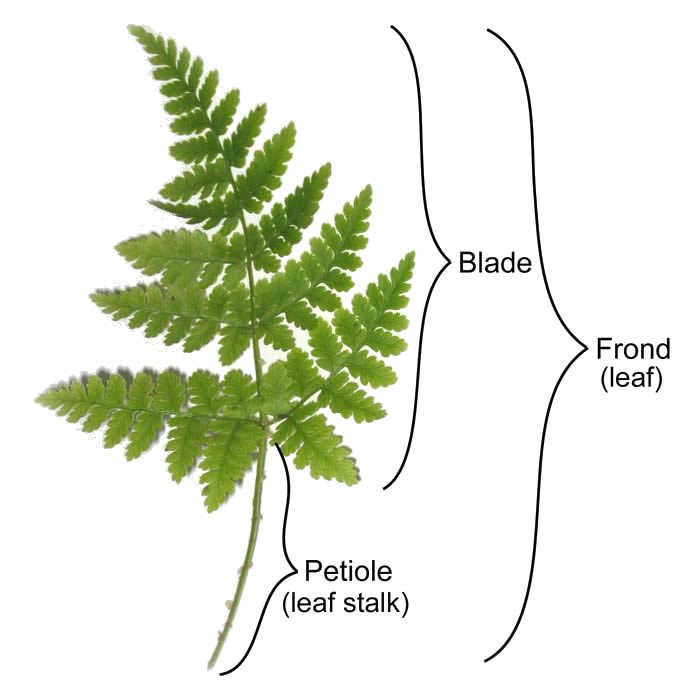

The leaves of ferns are often called fronds. Fronds are usually composed of a leafy bladeand petiole (leaf stalk). Leaf shape, size, texture and degree of complexity vary considerably from species to species.

The midribis the main axis of the blade, and the tip of the frond is its apex.

The blade may be variously divided, into segments called pinnae; single leaflets are pinna. Pinna may be further divided, the smallest segments are pinnules.

Pinnatifid

The frond is divided into segments divided from each other almost to the rachis.

Further Divided

Many ferns are known for their lacy appearance, these ferns have fronds that are even further divided.

- 2-pinnate (bipinnate): fronds are divided two times.

- 3-pinnate (tripinnate): fronds are divided three times.

- In cases were these secondary divisions do not cut to the rachis or the axis of the pinna the term pinnatifid is added to the degree of cutting to describe this type of frond dissection.

Examples of ferns displaying various degrees of leaf divisions:

Dimorphic Fronds

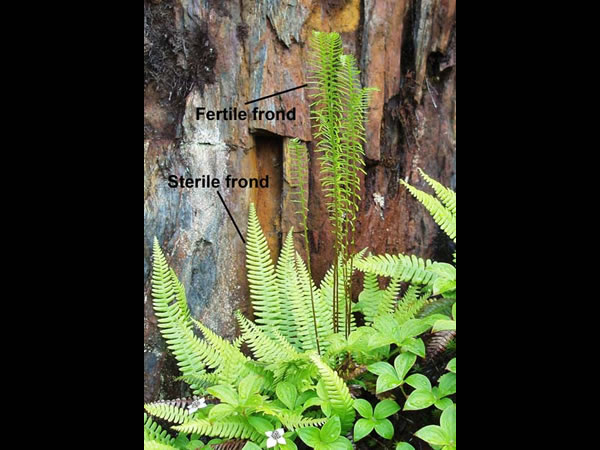

Some ferns have two kinds of fronds: fertile fronds (leaves with sporangia) and sterile fronds (leaves lacking sporangia). Ferns with two kinds of leaves are referred to as dimorphic. Examples of dimorphic ferns are deer fern (Blechnum spicant) and cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea).

Other ferns, such as the moonworts have sterile pinnae and fertile pinnae on the same leaf. This can be seen in the moonwort fern (Botrychium lunaria).

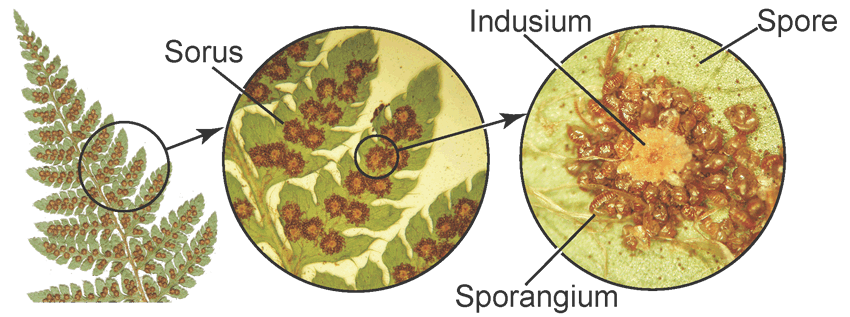

Fern Sori

Sori (singular: sorus) are groups of sporangia (singular: sporangium), which contain spores. Sori are usually found on the underside of the blade. Young sori are commonly covered by flaps of protective tissue called indusia (singular: indusium). See the following graphic.

Sori can vary considerably in shape, arrangement, location and covering depending on the kind of fern. These differences can be useful for identifying ferns. However, depending on the time of year, sori and indusia may not be useful characters because they may be too immature or too mature to be diagnostically useful.The following are some of the more common kinds of sori.

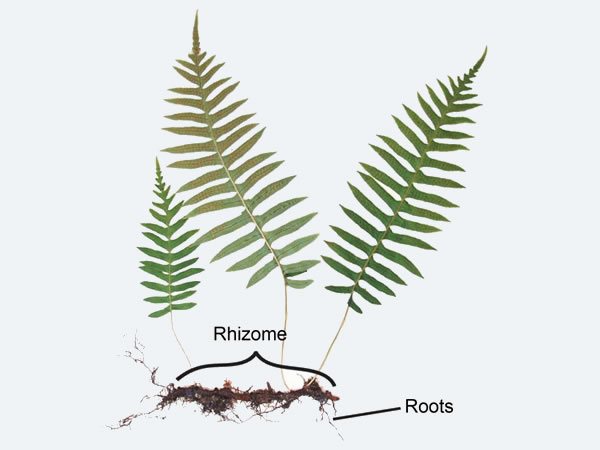

Fern Stems and Roots

Fern stems (rhizomes) are often inconspicuous because they generally grow below the surface of the substrate in which the fern is growing. This substrate can be soil, moss or duff. People often confuse rhizomes with roots. Fern roots are generally thin and wiry in texture and grow along the stem. They absorb water and nutrients and help secure the fern to its substrate.

Stems can be short-creeping with fronds that are somewhat scattered along the stem, such as the fragile fern; or, stems can be long-creeping resulting in fronds scattered along the stem, exemplified by the licorice fern.

Ferns are one of the oldest groups of plants on Earth, with a fossil record dating back to the middle Devonian (383-393 million years ago) (Taylor, Taylor, and Krings, 2009). Recent divergence time estimates suggest they may be even older, possibly having first evolved as far back as 430 mya (Testo and Sundue, 2016). However, despite the venerable age of the group as a whole, most of the earliest ferns have since gone extinct. Groups like the Rhacophytales, which were possibly some of the earliest progenitors of ferns, the ancient tree ferns Pseudosporochnales and Tempskya, and the small, bush-like Stauropterids have all long ago disappeared. The diversity of ferns we see today evolved relatively recently in geologic time, many of them in only the last 70 million years.

Today, ferns are the second-most diverse group of vascular plants on Earth, outnumbered only by flowering plants. With around 10,500 living species (PPG 1), ferns outnumber the remaining non-flowering vascular plants (the lycophytes and gymnosperms) by a factor of 4 to 1. How did ferns become so diverse, and what are the secrets to their success? What traits do they share in common, and how are they different from other groups of plants? What follows is a short primer on the biology of ferns, starting at the beginning, with how ferns first originated and evolved into the plants we see in the present, making special note of some of the groups that went extinct along the way. There are separate sections that cover topics ranging from fern morphology, phylogenetic relationships, and the fern lifecycle, along with the important role gametophytes play in the biology of ferns.